|

| Gregory I |

Rome had once been the powerful center of the civilized

world. It’s monuments attested to the

military victories and political will of its leaders to expand their empire and

protect and defend their holdings at any cost necessary. But that was all in a historic past that was

growing dimmer and dimmer with every year.

Rome the city was still standing and was an important symbol at least in

people’s collective memories, but by now it stood alone, vulnerable, and

unprotected by what remained of its own empire.

Into this time was Gregory born in the palace on the Caelian

hill that had belonged to his aristocratic family for generations. His family was well-connected to the wealth

and power that remained in Rome, his father being a senator (which must have

been more like a town council by this time) and his mother a part of the

highest social circles. Gregory’s family

was also Christian and had been so for some time. In the past, the family had produced two

popes, but Gregory had been carefully educated in law and was prepared for a

career as a public servant. By his

thirties he had reached the pinnacle of success attaining the office of prefect

of Rome which was the highest authority in the city.

But as history has its turning points, often these same

events become personal turning points as well.

Shortly before Gregory had become prefect of Rome, northern Italy had

been invaded by a people known as the Lombards.

The Lombards were a group from Scandinavia who had been migrating south

for centuries prior. They were a

Christianized people and had lived within the borders of the Roman empire for

so long that they had even adopted parts of Roman culture. But need and opportunity came together and in

568 they began to conquer and take the Italian peninsula for themselves. Although Italy still belonged to the Roman

Empire which was now situated to the east in Constantinople, they were

ill-prepared to defend this territory and little resistance was able to be made

against this warring people. This

problem doesn’t touch Rome or Gregory directly for nearly a decade, but year by

year it draws closer and nothing seems to be able to stop it.

In the meantime, when Gregory is in his forties, his father

dies and he inherits the family’s great wealth and landholdings. As he considers the turmoil of his times and

watches the great cities of Italy fall to siege, famine, and plague, he makes a

rather bold decision: he decides to retire from public life and become a Christian

monk. Since a vow of poverty was part of

being a monk, part and parcel with this decision was to take the family wealth

and endow 6 new monasteries dedicated to St. Andrew. Having done this, Gregory retires to the

monastery in Rome and embarks on his new vocation of religious life pursuing a

life of worship, prayer, contemplation, and acts of charity in preparation for

eternal life. It should be known that

Gregory thought the end of the world might be near (a thought many Christians

leaders have had during times of social upheaval and catastrophe) and if Christ

was to return soon he wanted to be found doing the business of the kingdom of

God rather than planning a better sewer and water system for Rome.

Gregory pursued his life as a monk with great enthusiasm and

unfortunately, like many man in this career, undermined his health by over

rigorous fasting and sleep deprivation; something that would plague him greatly

in later years. Soon Gregory was elected

by his fellow monks to be their abbot or spiritual leader and as his reputation

grew he was later ordained a deacon by the pope.

Later Pope Pelagius II asked him to be his representative at

the Emperor’s court in Constantinople. This

was a great honor but one in which Gregory was quite ‘tone deaf. He really never learned much Greek as Latin

had by his day become the sole language of Rome and he didn’t care much for the

pretensions of the Byzantine world. That to say, being a diplomat was not a good

match Gregory, but in this time as he frequently corresponded with the pope,

his writing skills were noticed and upon his recall to Rome, he was asked to

become the papal secretary and in this he served with great distinction.

|

| Gregory encounters Angle children |

It is during this time that Gregory and two brother monks

have an encounter that was to have an impact on the future history of

Europe. As they were passing by a slave

market (and yes, slavery was still practiced in the day) Gregory was impressed

with the beauty of some children that were being sold there. Having never seen people of this race he

enquired of one of his companions where they were from. Upon being told they Angles (English),

Gregory was said to have famously replied:

“Indeed they would not be Angli, but Angels if they were Christian.” Later when he became pope he promoted and

supported missions to many groups of people, but closest to his heart were the

English and the mission he sent there took hold and firmly tied the Christians

of England to Rome for the next thousand years until King Henry VIII made his

famous break with the papacy.

In the course of time as Gregory neared his 50th

birthday, a terrible plague struck the city of Rome taking as one of its

victims pope Pelagius II. Following his

death, a papal election was held and the people and clergy of Rome called on

Gregory to take the office of St. Peter.

Gregory at first resisted but saw the need and in 595 AD became the

first monk ever elected to the papacy.

|

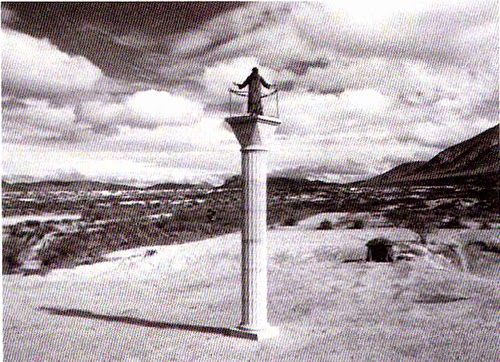

| Castel San Angelo today |

One of Gregory’s first acts was to hold a public procession

of humility and repentance before God in hopes of staying the plague that was

continuing to rage in the city. As the

procession neared the tomb of Hadrian a vision of the archangel Michael was

seen there putting his sword of destruction back in its sheath. Hadrian’s tomb, now known as the Castel San

Angelo, is decorated on top with a beautiful statue of an archangel to

commemorate this event. Surely it is

only a pious legend but it is an amazing coincidence that the plague did stop

that very day.

As pope, Gregory was an able administrator, tireless worker,

and visionary, bringing his monastic viewpoint to bear on the life of the

church as well as a mind that had been disciplined in prayer and

contemplation. His pontificate lasted

just short of 14 years but in that short span, he put an impress on the church

that it was hold throughout the Middle Ages and arguably in some ways still

holds. Let me share some concrete

examples.

|

| A great influence on music |

Although he did not invent Gregorian chant, Gregory was a

hymn writer and poet and wrote in a metered style that was easily chanted and

sung by choirs. Some of hymns are still

sung in Catholic liturgy and were made part of the mass.

The Latin mass was largely shaped by Gregory I. The theology of the Eucharist being an un-bloody

but actual repetition of Christ’s sacrifice for the sins of the world precedes

his day but Gregory fills the idea with even greater meaning. When it is served there is a reconciliation

of heaven and earth, time and eternity and a spiritual benefit is conferred

upon the living and the pious dead in a communion of the church.

In the early church there had long been the belief and

practice of offering prayers for the dead.

But in the Christian east purgatory was unknown. In the west it was an idea that was

embellished and came to blossom under Gregory.

To his mind, purgatory was a foregone conclusion. As each of the Christian faithful died there

were remaining sins and infirmities that needed purging before entrance into

glory. Gregory promoted the ideas of

saying 30 masses exclusively for the benefit of dead Christians as well as

adding almsgiving as an efficacious means of reducing your purgatory time or

that of a loved one. The provision for

this eventuality in the life of every Catholic unfortunately degenerated into a

form of Holy Fire Insurance over the next millennium.

|

| Dante was famous for his book on Purgatory |

Although Gregory would disclaim any jurisdiction over other

bishops around the Christian world he definitely held the view that the Bishop

of Rome has the commission of Peter and is above all other bishops in

Christendom as a first among equals. He

certainly advised other bishops, churches, kings, queens, and nobles, as if he

had jurisdiction over them and sometimes this was not greatly appreciated. Gregory also acted as a head of state. As Italy’s civil government continued to

suffer neglect and further barbarian attacks, Pope Gregory more or less made

the church the government. He organized

social welfare and military protection.

He also governed well the many papal lands around Italy, Europe, and

North Africa. This action set the stage

for the development of the later Papal States which were their own country with

the Pontiff as the governmental head.

Having actual territory under papal governance was a good thing under

Gregory as he used the lands to finance and provide food for the poor of Rome,

but later popes would become quite distracted with maintaining control of this

property to the point of abandoning their spiritual mission altogether. The point is Gregory may have disclaimed

being a monarchial pope in his writings and words, but is betrayed by his

actions despite his protestations.

Gregory was a prolific writer and promotes monasticism as

the biographer of St. Benedict of Nursia.

He also writes a book that directs priests in their spiritual ministry

called the Pastoral Rule. This book was very insightful and for

centuries the textbook on the care of souls.

Gregory is also the person who articulated the idea of the 7 deadly

sins: pride, covetousness, lust, envy,

gluttony, anger, sloth or apathy.

Although he borrowed the idea from the early church, he promoted it and

transmitted in his writing to future generations.

|

| Papal throne of Gregory I in Rome |

Pope Gregory was untiring in his service to the poor caring

for thousands in Rome. He stood up for

the rights of widows and orphans. When

he sat down to a meal, it was never before taking the food prepared for him off

the table and giving it to the hungry.

He even sold expensive chalices and sacred vessels belonging to the

church to help Rome’s impoverished.

Gregory personally punished himself if anyone died of starvation in his

city. Although some later popes were

very much guilty of indulging their pleasures, this pattern of charity for the

most part has remained a tradition within the papacy.

|

| Gregory I tomb in St. Peter's today |

Upon his death in 604, Gregory was immediately beatified

(made a saint by the church) by popular acclamation. In the 11th century the church

began referring to him as “the Great” a title that has only been applied to one

other pope in the entire history of the church.

In the 13th century Gregory I was declared a Doctor of the Latin Church in 1298 by then

Pope Boniface VIII (one of the few things he did right). “Doctor” in Latin means a teacher and so this

classification denotes an important contribution was made to the teaching of

the church in their lifetimes or through their writings. The Protestant 19th century

historian Philip Schaff sums up his life well:

“Goodness is the highest kind of greatness, and the church has done

right in according the title of great to him rather than other popes of

superior intellectual power.”

Sources

Bede. A History of the English Church and

People. (London : Penguin Books,

1968)

Collins, Roger. Early Medieval Europe 300-1000. (New

York : Palgrave Macmillan, 2010)

Dawson, Christopher. Religion and the Rise of Western

Culture. (New York : Doubleday,

1957)

“Gregory I”. Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological, and

Ecclesiastical Literature. McClintock

and Strong Eds. (Grand Rapids: Baker

Books, 1981)

Gregory the Great, bishop of Rome. The

Pastoral Rule. James Barmby D.D.

trans. (Peabody : Hendrickson

Publishers, 2004)

Ferguson, Everett. Church History Vol. 1: Christ to

Pre-Reformation. (Grand Rapids : Zondervan, 2013)

Kelly, J.N.D. The Oxford Dictionary of Popes. (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1986)

La Due, William J. The Chair of St. Peter: A History of the

Papacy. (Maryknoll : Orbis, 1999)

Peterson, Curtis, Lang and.

The 100 Most Important Events in

Christian History. (Grand Rapids :

Revell, 1994).

Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church vol. 4:

Medieval Christianity 590-1073. (Grand Rapids : Eerdmanns, 1994)