|

| J. N. Darby |

You have probably heard of Hal Lindsey’s Late Great Planet Earth or Lahaye and

Jenkins’ Left Behind series or maybe

you even own a Scofield Reference Bible,

but chances are you’ve never heard of the man behind the theology upon which each

of these well-known books are based. I’m

not speaking of Jesus, or Saints Peter and Paul, but rather John Nelson Darby

an Irish cleric whose method of Bible interpretation in the 19th

century became the most widely accepted approach to understanding future

prophecy among evangelical Christians in the 20th and 21st

centuries. Who was this man and why

after 18 centuries of Christianity did he see something so many others had

missed or misunderstood?

John Nelson Darby (1800-1882) was born to an aristocratic

family that were distant relatives of the famous English Navy Admiral Lord

Nelson in 1800. At age 14 he was

enrolled in university studies and achieved a degree in Law. Around age 20 Darby has what would be

properly termed a radical conversion experience and amid much opposition from

his wealthy father, he gave up law to pursue a call to ministry. He was disowned and disinherited by his

father, but a wealthy uncle befriended him and patronized his ministerial

studies.

Upon ordination he worked as a curate (priest) in the Church

of Ireland. After several years Darby became

quite disillusioned with the established church and began to align himself with

those of a separatist (those Christians outside the established church)

mindset. His disillusionment was

largely over the gap he saw between the spiritual orientation of the church in

the Bible versus the more worldly orientation of the visible church that is

aligned with the state. Although he

remained in the state church for several more years, eventually he made a break

joining with other Christians in forming a fellowship called The Brethren.

| |||||

| Hal Lindsey |

The Brethren formed chapters in Plymouth England and Dublin

Ireland and because the larger group was found in England, they were named by

outsiders the Plymouth Brethren. Darby

later in life would have a strong doctrinal disagreement with the leadership

and broke away from them forming another sect of Brethren known to some as the

Darbyites. Brethren theology was in full

agreement with most tenets of Protestant theology but did have two distinctions

that have always tended to keep them a smaller denomination. First of all they held the belief that the

office of pastor is Biblically unwarranted and that all believers in a church

should be free to preach if led by the Spirit to do so. This is certainly true in the sense that

Christianity does not teach an exclusive priesthood by dint of proper

ordination (as is believed by churches holding to the doctrine of apostolic

succession) but the pastoral epistles of Timothy and Titus do in fact

anticipate and suggest a trained and paid teaching ministry in the church. Secondly, there is a belief called “the ruin

of the church.” This suggests that the

visible church on earth is largely corrupt and beyond hope of revival. What true Christians should do is come out of

their corrupt denominational churches and seek the fellowship and encouragement

of those walking in the truth of God’s word.

The true Church is not to be confounded with its visible manifestations

on earth but rather is composed as a spiritual body of all true Christians who

are in union with Christ no matter what their denomination.

Darby and the others in this movement did live in an

environment where the visible church, such as the Church of England and Ireland,

was corrupted by its relationship to the government. But Darby was quite surprised to find in

America that very few people felt they were involved in a corrupt

denomination. But the American

experience was vastly different since there never was the connection between

church and state. Dependence on growth

from disaffected Christians along with holding an identity of being the purest

strain of Christianity led to many divisions and offenses which have conspired

to keep this denomination small even today.

This brings us to Darby’s unique theological contribution to

the evangelical church. There is no

written evidence of exactly when J. N. Darby came to his conclusions, but what

is known is that during his 1840 Lausanne lectures on a mission to Switzerland

he really developed his theology in a systematic way. Darby accepted all the main tenets of Protestantism and was

Calvinistic in many things. He is

credited with introducing a wider audience to dispensationalism—where salvation

history is divided into separate periods where God deals with humanity in

varying ways. Darby did not invent

dispensational thought but did much to popularize it. There is a bit of negativity to

dispensational thinking for in each dispensation man does not succeed in

carrying out what God has ordered him to do.

Maybe this isn’t negative so much as giving men no reason for optimism

about their spiritual state before a holy God.

If it were not for the grace and patience of God, we would all be toast.

How this touches on Darby’s innovative thought is

two-fold. First of all it was long held

by Catholics and most Protestants that because Israel rejected Jesus as their

messiah in the 1st century, all the promises and blessings of that

covenant were nullified forever in favor of the new covenant with the

church. Darby was very much aware of

this thought but saw it differently when looked at through the lens of

dispensationalism. Christ had during his

earthly sojourn had a two-fold ministry.

He was fully offering Himself as Israel’s Messiah while simultaneously

offering Himself as the Lord of Church knowing that he would be rejected.

In this there emerges a dispensation hidden to the Old

Testament prophets that is known as the church age. This age is an indefinite pause in the

prophetic time clock of Daniel (see Daniel chapter 9) where 70 weeks of years

are decreed until all prophecy will be fulfilled and God’s plan for Israel will

be brought to completion. The day Jesus

entered Jerusalem for the last time marked the 69th week, but 1800

years have passed since that time and human history continues. But both Daniel and Revelation speak of a

final week of years where God will pour out his wrath upon the earth in

judgment for sin and rebellion against Him and also to finally bring Israel to

repentance that they might embrace Jesus Christ their messiah. Therefore, this is a time of grace when the

Gospel of Christ is proclaimed among all

nations before this final week (see Mark 16).

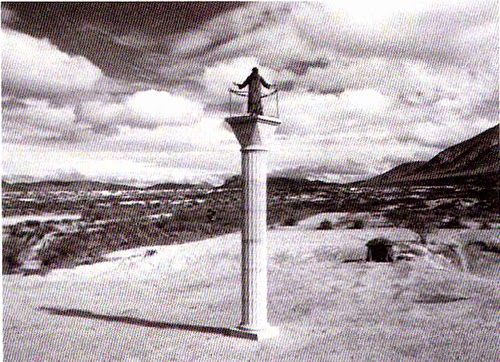

|

| Depiction of the Rapture |

Thus, Darby takes the Rapture (described in 1 Thessalonians

4) as an event only touching those faithful to Christ (in both Testaments) and

as separate from Christ’s visible return to set up a world kingdom in Jerusalem

in fulfillment of the promises of the Old Testament. It is a secret in that Christ does not come

to earth but instead calls the church up to himself ending the church age and

beginning the 70th week of Daniel which ends prophecy and ushers in

the golden age of Christ ruling the earth directly. Not seen by all people, the sudden

disappearance of millions on the earth who are Christian, puts the world into

chaos and sets the stage for the future development of a state run by the

Antichrist. Because the rapture does not

depend on the fulfillment of any prophecy it can happen at any time. A corollary of this is that events described

in the book of Revelation are all future and entail events that will unfold

after the rapture of the church. Another implication of this from Darby’s

perspective would have been a restored Israel, something we see in our time but

he did not yet see in his. The

interpretive key it seems is that Darby was able to separate out the verses of

the prophets and of Jesus that apply to Israel alone and the church alone. In not confounding the two and thinking in

terms of dispensations, Darby saw something that many others had not.

|

| C. I. Scofield |

Darby’s great success was not his work with the Brethren,

but rather the broad reach of his ideas.

Evangelicals with a literal hermeneutic of the Bible readily adopted his

theology. These ideas were in turn

popularized by the Scofield Reference Bible, The Niagara Bible

Conferences, D. L. Moody, and many Bible

Colleges and Seminaries. Nearly all

fundamentalists in the 20th century adhered to his basic doctrines

and though somewhat modified are still

widely held by most evangelicals today.

Sources

“John N. Darby” Dictionary

of Christian Biography. Michael

Walsh Ed. (Collegeville : The Liturgical

Press, 2001)

“John Nelson Darby” New Dictionary of Theology. Ferguson, Wright, and Packer Eds. (Downers Grove : Intervarsity Press, 1988)

“John Nelson Darby” Who’s Who in Christianity. Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok Ed.

(London : Routledge Press, 1998)

Knight, Frances. The Church in the Nineteenth Century. (London : I.B. Tauris, 2008)

“Plymouth Brethren or Darbyites” Cyclopedia

of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. McClintock and Strong Eds. (Grand Rapids : Baker Books, 1981)

“J.N. Darby” Biographical Dictionary of Evangelicals. Larsen, Bebbington, and Noll Eds. (Downers Grove : Intervarsity Press, 2003)

Olson, Roger E. The Story of Christian Theology : Twenty

Centuries of Tradition and Reform. (Downers Grove : Intervarsity Press, 1999)

Sandeen, Ernest R. The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American

Millenarianism 1800-1930. (Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1970)

Sweetnam, Mark and Crawford Gribben. “J.N. Darby and the Irish Origins of

Dispensationalism”. www.etsjets.org. Pp. 569-577. Sept. 2009.

Web 07.2014

Woodbridge, John D. and

Frank A. James III. Church History : From Pre-Reformation to the

Present Day. (Grand Rapids :

Zondervan, 2013)